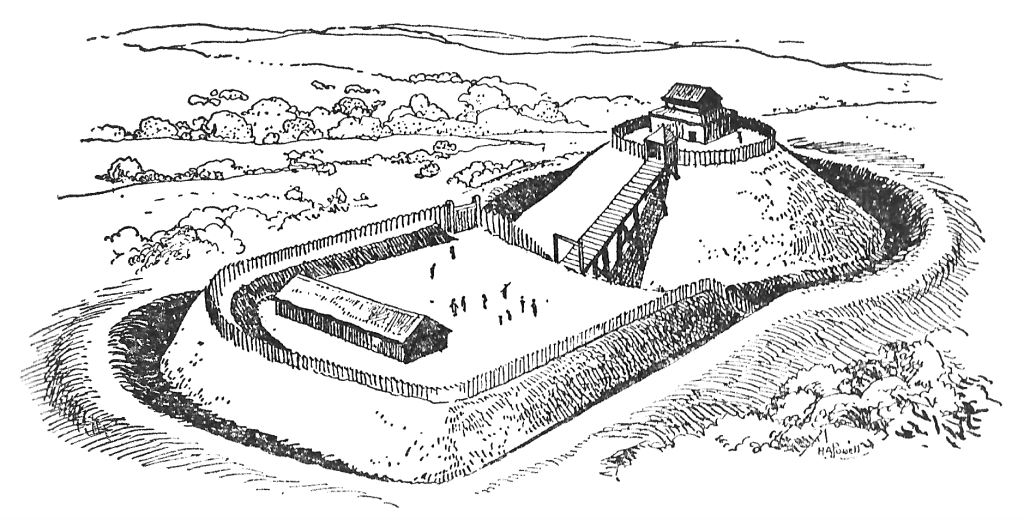

The First Castle

Little is known about the first Alnwick castle. Probably constructed by the De Vescys, it would have been a motte and bailey, and may initially have been a timber construction. By 1138 a chronicler refers to Alnwick Castle as ‘most heavily fortified’, which implies that by this date, timber had been replaced by stone.

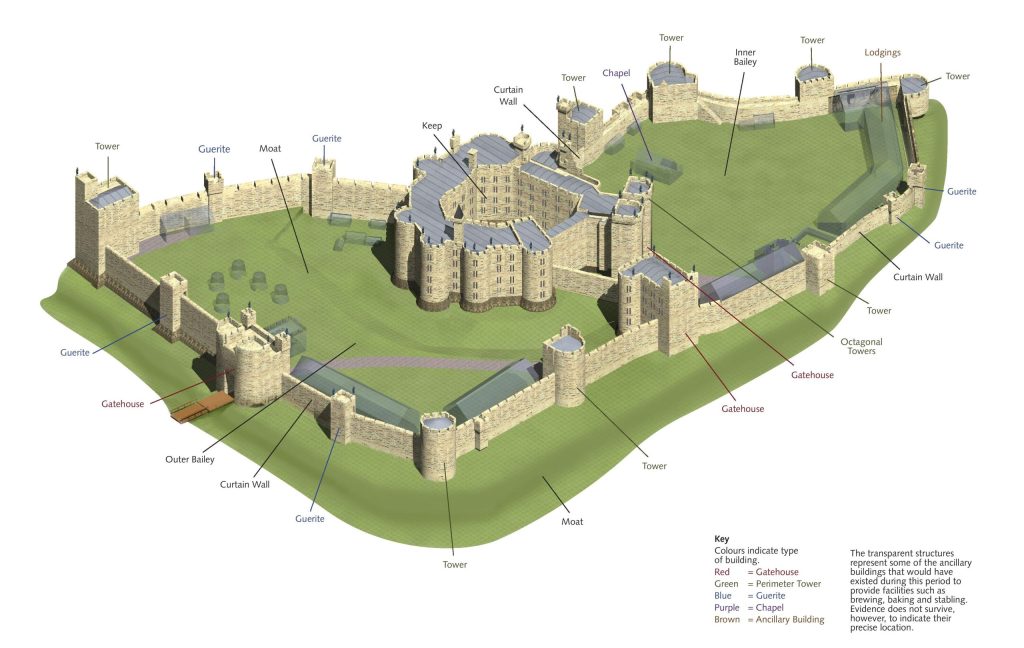

The Castle as a Border Fortress

In 1309, Henry Percy, great-great grandfather of Hotspur, purchased a typical Norman-style castle of motte and bailey form. In the following 40 years he and his son converted it into a mighty border fortress. They added towers and guerites around its curtain walls with a strong gatehouse at the entrance and a concealed postern gate to the rear. The gateway to the keep was strengthened with the addition of two massive octagonal towers.

Stone figures were added to the tops of the battlements, as was fashionable at that time, either for ornament, or to confuse attackers. This was a medieval device that the 1st Duchess was to copy to excess in the more fanciful mid-18th century castle restoration.

The Barbican of Alnwick Castle is one of the finest surviving structures of its type in Britain. It played a major role in securing the defence of the Castle. There is debate as to its exact date. Architectural historians posit an early 14th century date and link it with the major building works then undertaken by the first Lord Percy of Alnwick and his son. Archival evidence, however, shows that building work was carried out in the late 15th century and that the 4th Earl’s badge was placed over the entrance in 1475.

The 4th Earl had alterations and repairs carried out to adapt the Barbican to the latest tactics of warfare (especially considering that the castle was besieged and changed hands no fewer than five times between 1462 and 1464). The town’s defences were also being strengthened during this period, following devastating raids by the Scots in the first half of the 15th century.

The Barbican had numerous purposes. It stood as the first line of defence at the castle’s most vulnerable spot. Up until the 18th century this was the only entrance to the castle, apart from the concealed postern gate. For counter-attack, it was possible within its high walls, safe from enemy view, for castle forces to mass in order to spring an assault on besiegers.

The Barbican controlled everyday access to the castle by funnelling approaching traffic on foot, horseback or in a wagon, onto the causeway within its walls. Once the outer door was closed, the castle porter and Gatehouse guards could check all visitors. Without this system, the Gatehouse stood, in times of continual border disruption, an easy target for even a small determined force of raiders.

By the early 16th century, development of powerful field cannon had made the castle susceptible to siege warfare but, as a stronghold in local border conflict, the castle with its barbican still remained formidable.

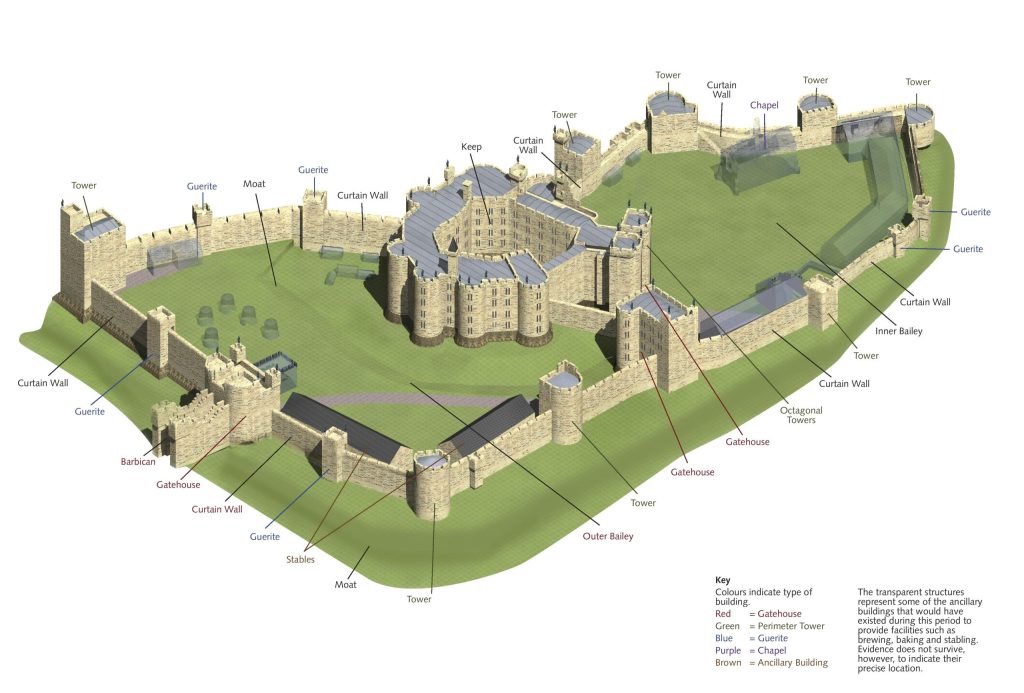

The Castle in 1567

Early in the 16th century, the castle was assessed and written off in defensive terms as not liable to abide the force of any shot or to hold out any time if it should be assaulted. In 1567 the 7th Earl employed George Clarkson to survey the castle and his northern estates. His detailed account, together with the plans drawn by Treswell in 1608, enable us to be quite accurate about how the castle looked and what the buildings were used for during this period. Clarkson also describes the condition of the buildings, mentioning that the Ravine Tower was so rente that it is mooche like to fall, as indeed it did later in the 17th century.

The Castle in 1690

During the 17th century, the castle fell into disrepair, both through neglect because the Percy family was mainly resident in the south, and through damages done in wartime. An eye witness account records the damage done to the castle during the Civil War:

I cannot sufficiently relate the Augmentation of the spoyle of his Lordship’s howse, eaven by both parties, burning wood, takeing away all the Iron barrs, bolts and Lockes of doores and doore bands to great dammage of the howse, distroying of meadowes soe as I knowe not where to make any provisions of hay for your use, nor dare I adventure to repare or put any thing in good order by reason of badnes of tymes and the incertainyty of amendment (the lead of the house is yet well saved and that is all).

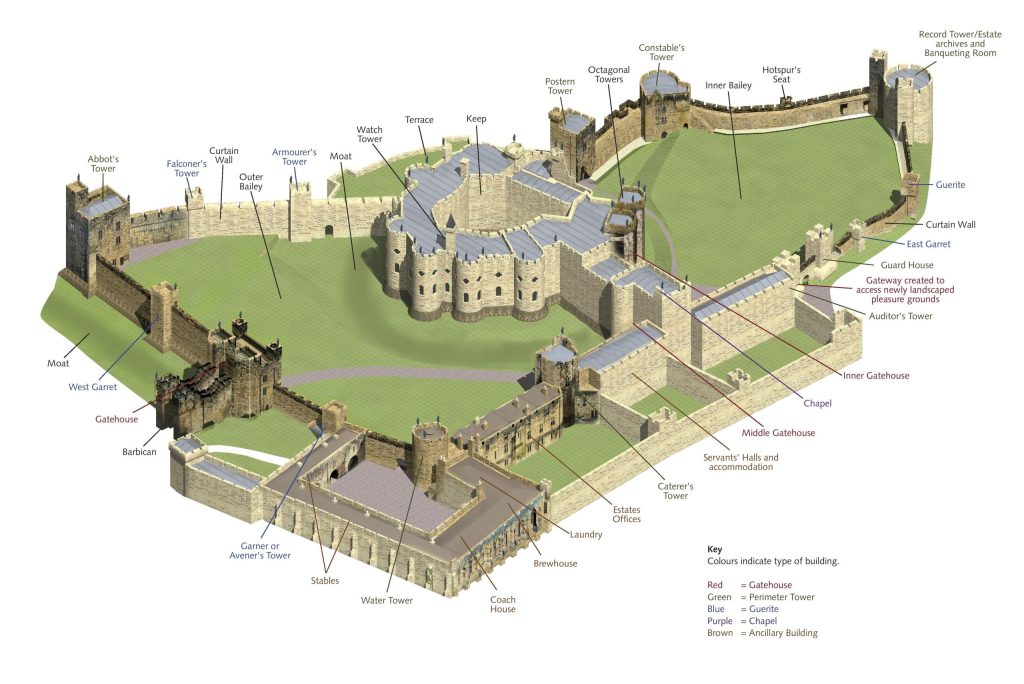

The Castle in 1776

By the 1750s the castle was in a state of semi-ruin. A revival of the Percy name and fortune, however, in the mid 18th century led to a grand restoration of the Castle as a fairy-gothick palace, a fitting home for the newly elevated 1st Duke and Duchess of Northumberland. James Paine and subsequently Robert Adam, both prominent architects of the day, were employed to reshape the Castle. The Baileys were cleared of Stables, Chapel and ancillary buildings. Land was bought up to expand the Castle grounds and a stable block and Estates Office were built outside the original curtain walls. A new gateway was formed leading from the Inner Bailey, across the moat, to the new Castle gardens. A Terrace was also constructed facing the river, from which to admire the newly designed landscape.

Weirs were built on the river Aln to slow the water flow with the effect of enhancing the landscape and providing a reflective surface for the newly restored castle.

The 1st Duchess visited Alnwick each summer, particularly enjoying her carriage rides throughout the surrounding countryside. In one of her notebooks she lists and names no fewer than 98 different rides that could be made from the castle.

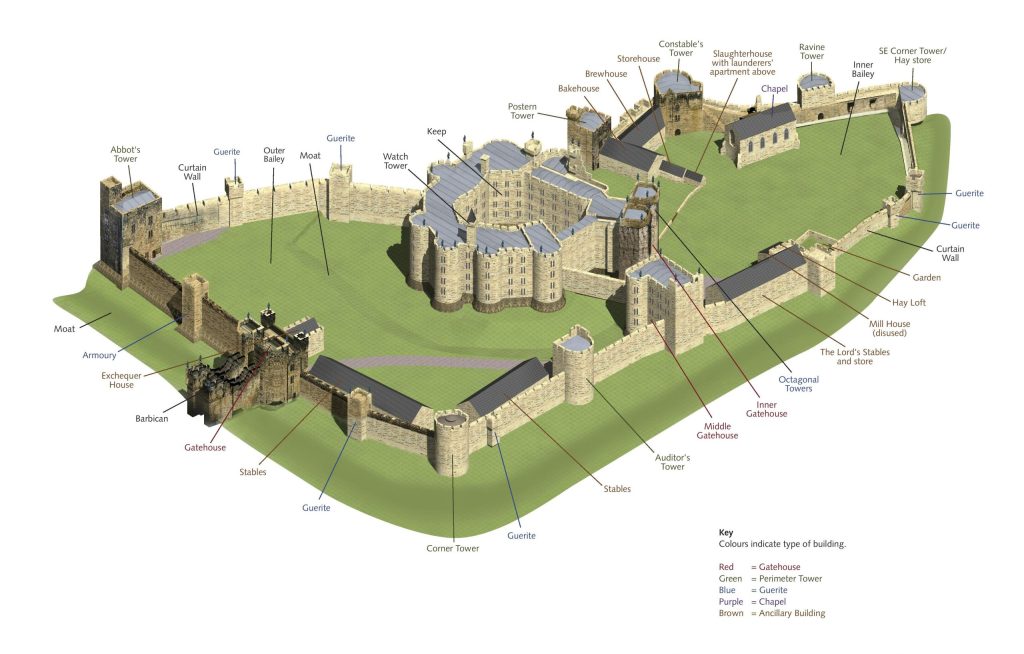

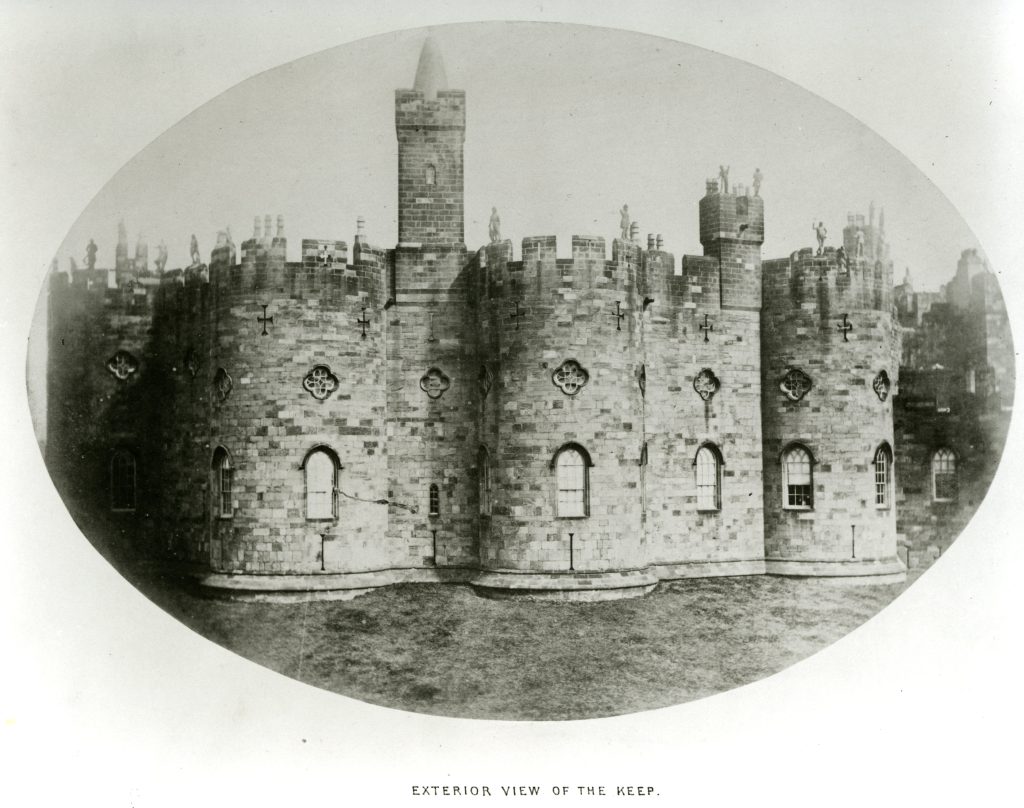

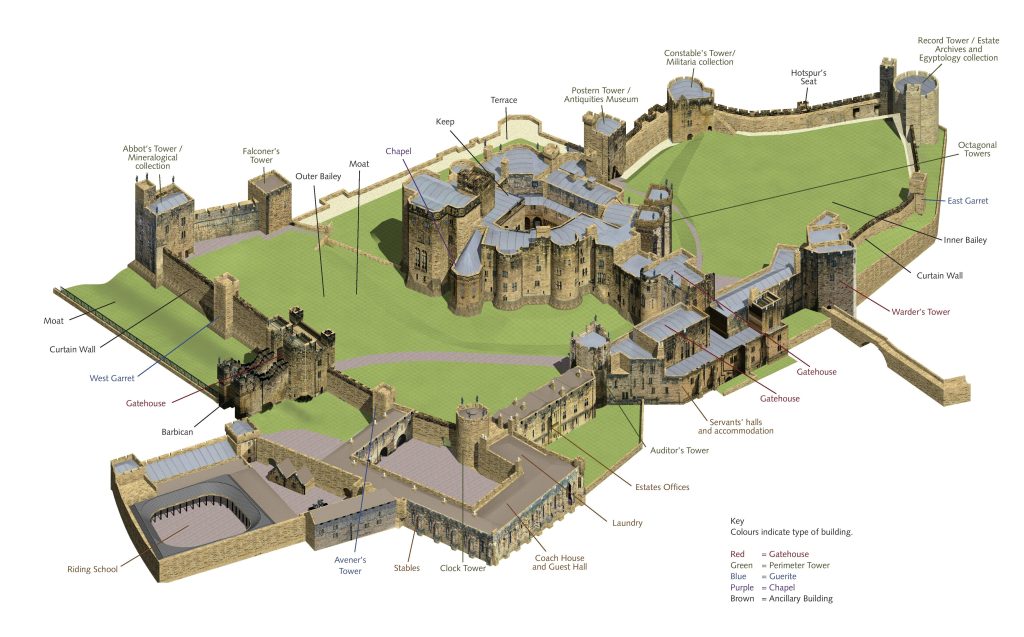

The Castle in 1865

The 4th Duke disliked the ‘fairytale gothick‘ style and inconvenience of the castle created by the restoration undertaken a century previously.

Anthony Salvin was employed as Architect to restore an austere mediaeval appearance to the exterior, whilst the State Room interiors were enacted in an exuberant Italian Cinquecento style under the direction of Luigi Canina, Giovanni Montiroli and Alessandro Mantovani.

The Keep was significantly altered by the addition of the Prudhoe Tower and the Chapel, and the Riding School was added beyond the Stable Yard, expanding the Castle site further. Improvements were made across the castle site exploiting new technologies of the Victorian age.

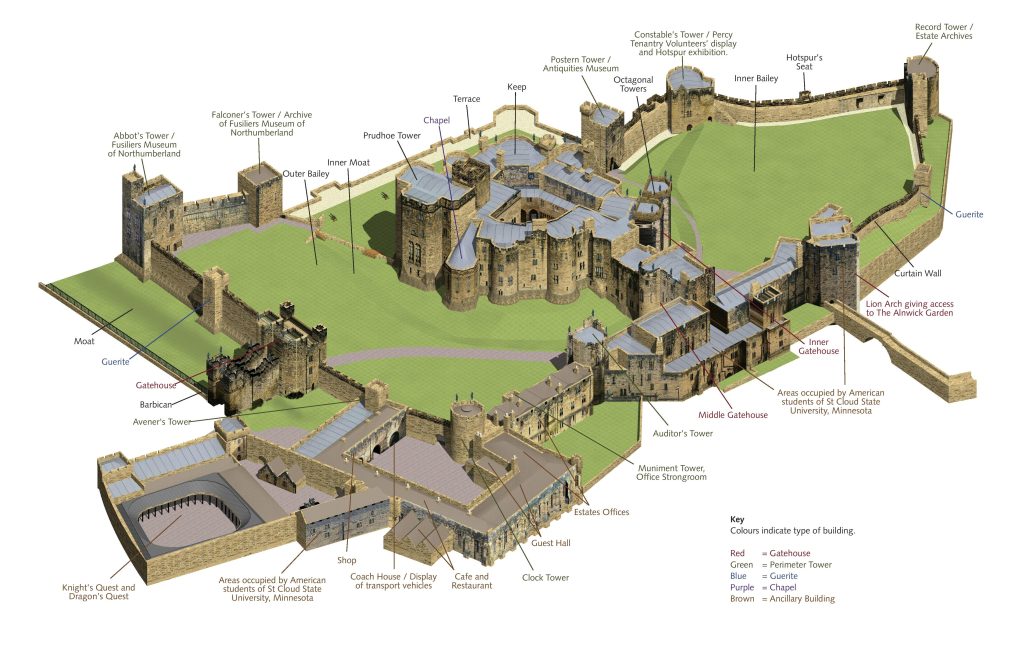

The Castle in more recent times

By the time Hugh Percy entered the dukedom in 1940, the large team of live-in domestic servants he had known as a boy was no longer in existence. This left vast areas of the castle unused and unoccupied. These provided facilities, first for the accommodation of Alnwick Teacher Training College, and then, from 1981, for St Cloud State University students from Minnesota in the United States.

Today, the Duke and his family share their home with Estates Office staff, American students from St Cloud State University residential programme and the general public.

Recent years have witnessed an extensive programme of conservation, repair and refurbishment to the fabric of the building, both exterior and interior. Roof leads have been replaced; essential masonry repair and re-pointing has been undertaken, as well as conservation work and refurbishment of the interiors. Such works both preserve the castle and continue its development.

Much of the information above came from Northumberland Estate’s publication ALNWICK CASTLE – 700 years of change who kindly gave permission to use the material.