This North Eastern Railway branch railway is occasionally, though incorrectly, referred to as the Coldstream Branch, as the town of Coldstream lies entirely north of the Scottish Border, whereas Cornhill-on-Tweed lies on the English side, its station being on the line from Tweedmouth to Kelso and then St. Boswells.

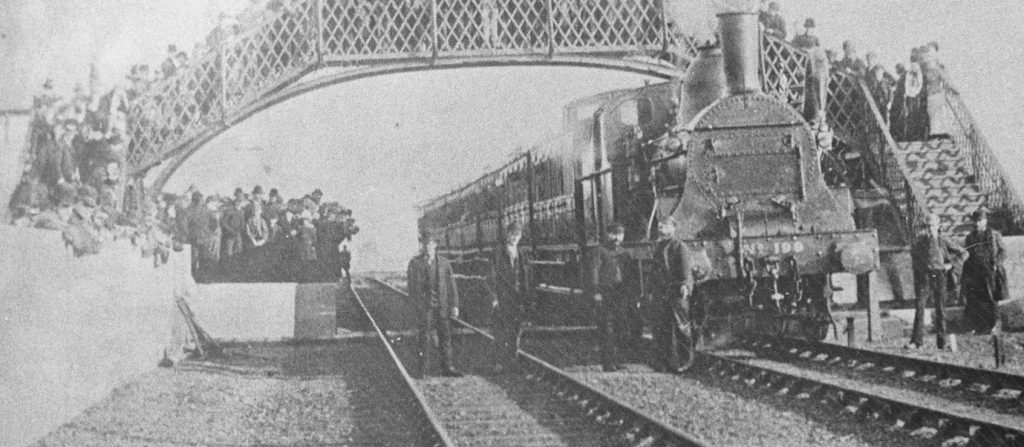

It was built largely by the contractors, Meakins and Dean and opened throughout, between Alnwick and Cornhill, on 5th September 1887.

The construction involved the building of Edlingham viaduct and the Hillheads Tunnel between Edlingham and Whittingham.

The Hillheads Tunnel, 351 yards in length, and the Edlingham Viaduct, with five 40’ spans and some 60’ high, were the major engineering works on the line. In addition to these there were 101 bridges and culverts, some of which, such as the bridges over the Wooler Burn and the River Breamish were substantial. In addition there were deep cuttings especially near the line’s summit some 4 miles from Alnwick. The approaches to the summit involved some steep gradients of 1 in 50.

There were ten intermediate stations between Alnwick and Cornhill:-

- Edlingham

- Whittingham

- Glanton

- Hedgeley

- Wooperton

- Ilderton

- Wooler

- Akeld

- Kirknewton

- Mindrum

Whittingham station was unique on the line in being constructed with an island platform with two faces. The other stations had a single platform placed on one side of the track. As a result this was the only station on the line where two passenger trains were allowed to pass. At the other stations it was possible for a passenger train to pass a goods train, or for two goods trains to pass each other.

All of the station buildings, also the goods sheds, were substantially built from local stone (and many of them still stand today). Loops and sidings were provided at all stations for the goods traffic on the line.

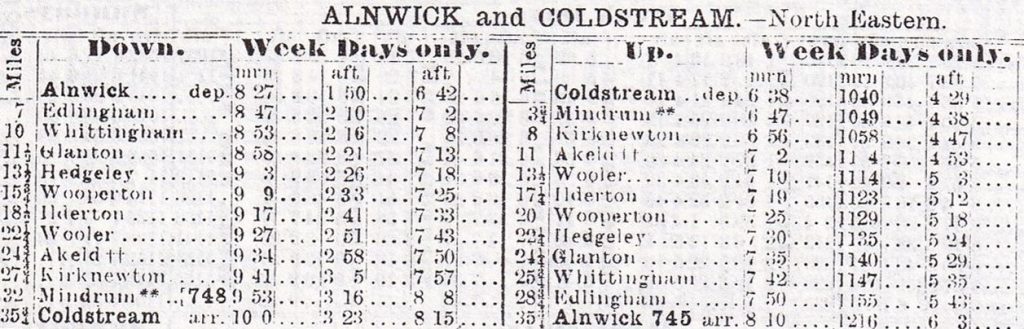

The passenger train service, which ran between 5th September 1887 and 22nd September 1930 generally consisted of three trains in each direction; during some years there was a fourth passenger train in one direction only. Note that this July 1922 timetable, reproduced from ‘Bradshaw’s Guide’ refers to Cornhill station as ‘Coldstream’!

Although the distance, as the crow flies, between Alnwick and Cornhill was just 26 miles, the line’s curvature resulted in a distance of about 35¾ by rail. As can be seen from the timetable extract, journeys between the two end-stations took about 1½ hours. Except on special days, such as show or fair days, passenger traffic was not considerable and the service was withdrawn after just over 40 years.

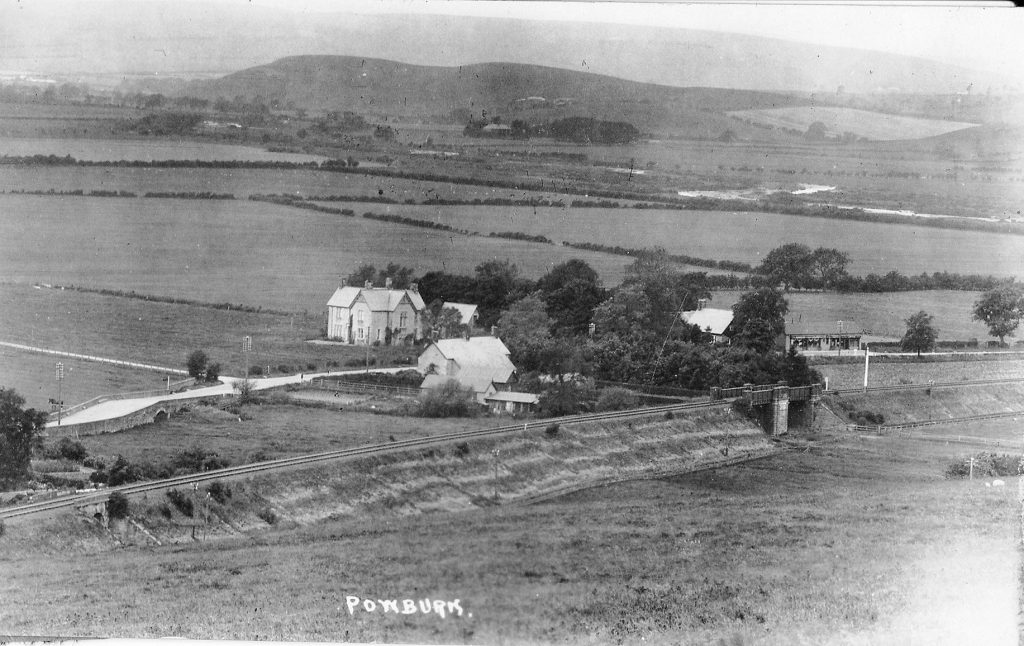

As the following photograph shows the entire line ran through countryside with a low population density and so it is of no great surprise that the LNER, on reviewing its traffic flows, decided that passenger services on the line were losing money and hence they ceased in the early 1930s. The last passenger trains on the line were ‘enthusiast specials’ which covered the part of the line between Cornhill and Wooler in the early 1960s.

Goods traffic, however, was more remunerative and goods services lasted for years after the passenger traffic ceased. Serving a largely rural area it is no surprise that agricultural activities relied on the railway: farm machinery and fertilisers arrived by rail and livestock, principally sheep, was carried. In addition there were quarries close to the line. Doddington Quarry produced fine building stone which was transported to destinations as far away as Edinburgh, whilst Scotts’ Quarry near Wooler produced a fine roadstone used both in Northumberland and in the border counties. Scotts had their own siding laid at Wooler station whilst stone from Doddington was transferred from carts to rail vehicles by the crane in Wooler station sidings. A rail-connected brick and tile works was located very close to Whittingham station and ‘exported’ its products by goods train. Another source of traffic for the railway developed in the middle of World War 1. The Canadian Forestry Corps had two local camps, with the foresters cutting down trees to provide timber for the war effort including both pit props and timber for military purposes. The camps were located at Chillingham and Thrunton. Timber from Chillingham was transported by lorry to Ilderton station whilst a siding was laid just to the south of Whittingham station to supply the Canadians’ sawmill which received the tree trunks (cut on Thrunton Crag) via a standard gauge railway. This employed a steam locomotive to haul the trains. Goods trains took the timber away via the line to Alnwick.

Normally a goods train worked from Alnwick as far as Wooler. Here it met the goods coming in the opposite direction from Tweedmouth and Cornhill. After exchanging and collecting goods the two trains made their way back to the originating station.

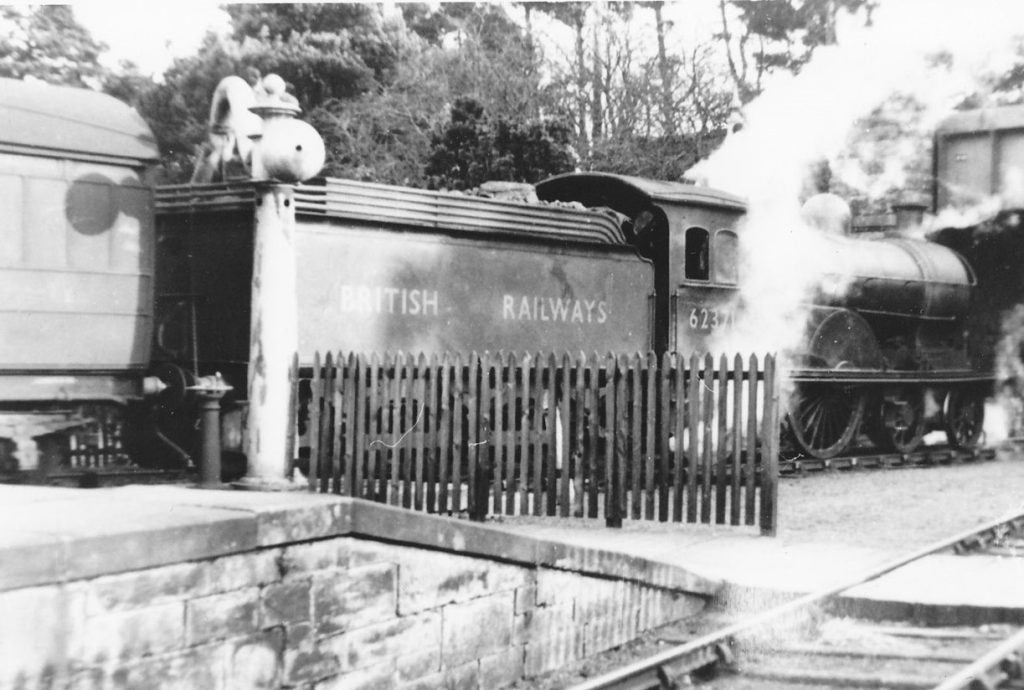

Some activity at two of the branch stations! On the left is a lady porter at Wooperton station probably in the first few years of the 20th century. Note the flower beds on the platform and the porter’s ‘NER’ cap badge. In the second photograph D20 4-4-0 number 62371, based at Alnmouth loco shed, awaits departure from Whittingham station with the goods train returning to Alnwick. Note the water crane in the background which has probably been use to top up the tender tank. This photograph was taken in the early 1950s as the engine’s tender is lettered rather than bearing the ‘lion and wheel’ emblem.

However the pattern of goods train working was to change in 1949. After very heavy rain the track was washed out to the north of Ilderton station. British Railways obviously considered that the cost of reinstatement of the through route could not be justified on such a lightly used line. Instead the northern part of the line was worked as a branch line between Cornhill and Wooler. The southern part of the line was worked between Alnwick and Ilderton, though the lack of a ‘run-round’ loop meant that the goods had to be propelled, on the outward journey, from Wooperton to Ilderton. The Alnwick to Ilderton section was to close in March 1953, whilst the northern section from Cornhill to Wooler survived until March 1965 with engines from Tweedmouth shed providing the locomotives for the goods trains and for the occasional enthusiast special train.

A tailpiece! The Alnwick to Cornhill line was hardly a line on which to expect large locomotives. However there is one recorded instance of a large Pacific locomotive, hauling a ‘Scotch Express’ traversing the line; the incident was reported in a local newspaper!

After heavy rain the direct line between Alnmouth and Tweedmouth became impassable. A decision was made for the train to run from Alnmouth to Alnwick. Here it was necessary for the long train to be split into two so that the engine could run around to the other end of the train. The Pacific was too large for the Alnwick turntable so it had to haul its heavy train onto the Cornhill branch running tender-first! It headed up the bank towards Rugley Woods at low speed, finally stalling because of the steep 1 in 50 gradient. The fireman walked back to Alnwick station and help was summoned from Alnmouth. The only locomotives available to assist were two D40 4-4-0s, which, with their large driving wheels, were hardly suitable as ‘banking engines’! However they attached to the rear of the train and the train headed over the summit and on towards Cornhill. An inspector at this station nearly had apoplexy when he saw the cavalcade arriving as the Pacific locomotive was officially too heavy for the branch line! However he allowed the train to proceed onwards to Tweedmouth where the locomotive ran round its train again. Now it could proceed chimney-first through Berwick and on to Edinburgh, no doubt much to the relief of the bemused passengers!

Most of the photographs are from the Aln Valley Railway’s photographic archive, including some obtained from the Armstrong Railway Photographic Trust; the commercial postcard is from the Roger Jermy collection.

The full history of this line is related in the book entitled ‘The Alnwick and Cornhill Railway’ written by John Addyman and John Mallon and published in 2007 by The North Eastern Railway Association.