The need to isolate those with a contagious disease has long been understood, and “pest houses” or “plague houses” date back to the 1400s. In response to the Great Plague of 1665 Charles II stipulated that every parish must identify a house for isolation of those with the “pestilence”. Specialist isolation hospitals were introduced in London in the late 18th century, and elsewhere in the 19th century. However, most contagious diseases have always been treated at home.

Alnwick Dispensary was established in 1815, and had become an infirmary in 1849. Alnwick Union Workhouse was built on Wagonway Road in 1841, with a hospital at the eastern end of the site. It is well-known that Alnwick dealt with a serious outbreak of Cholera in 1849. We begin the story of Alnwick’s Fever Hospital a generation later, in the late 1860s. Back then some in Alnwick who caught a contagious disease might be treated on a charitable basis: in either the infirmary, or in the workhouse. Most would organise their own treatment and care at home.

At that time, in Alnwick, the idea of establishing a separate Fever Hospital was controversial. Some felt that the infirmary provided all the care necessary. Some were concerned that the resources needed to build and run a Fever Hospital would divert medical staff, and donations away from other causes.

However, the greatest anxiety was that a Fever Hospital in Alnwick would attract infection into town. People feared that, during an epidemic, patients with contagious diseases would arrive in Alnwick from the surrounding countryside and become a burden on the town. The doctors and other medical staff who treated them would spread the infection to their other patients. Trade would suffer as people from surrounding areas stayed away to avoid the the risk of becoming infected themselves.

In 1871 the Infirmary was both dispensing medication and treating infectious diseases. There was a recognition that having these two functions in one building was not ideal when people ought to be isolated. However, the combination reflected the original charitable purpose. Governors were divided on how best to proceed, and they rejected the proposal to establish a separate Fever Hospital by small majority on a vote of 22:17.

As time went on, various alternatives were considered. One way of isolating infection was to acquire a temporary “Iron Hospital”. Corrugated iron structures, such as this, could be erected quickly, retained for long enough to deal with an epidemic, then removed when they were no longer necessary. That idea was rejected on the basis that it was impractical. The suppliers of such hospitals were in London – too far away.

The next important change was that the Public Health Act of 1875 allowed a local authority to establish a Fever Hospital. In 1877 the Rural Sanitary Authority suggested to the Alnwick Board of Health that they join forces to do this. They were rebuffed. In 1880 an independent committee advised that Alnwick needed to make some provision for isolating contagious diseases, but found it impractical to introduce a fever ward within the existing infirmary. Nothing was done.

Then in 1885, there was an event that helped to shift opinion. A railway navvy working on the Alnwick / Cornhill branch at Edlingham was diagnosed with Scarlet Fever. There was nowhere to isolate him. No Fever Hospital had been established, and there was no fever ward in the Alnwick Infirmary. He had to be accommodated in Alnwick Workhouse – where he could not be isolated.

It was clear that failing to make provision would not keep infection away from Alnwick. Within 18 months a site for a fever hospital had been identified, in a field off the Wagonway. The Duke agreed to provide the land, and the necessary approvals were obtained from the Medical Officer of Health, Local Government Board and Government Inspector.

The site was reasonably accessible from the town, but not close to the housing that existed at the time. Nevertheless, over 100 inhabitants of Duke Street, East and West Parade signed a petition objecting to the location. The objectors lived close to an existing hospital at the workhouse, and an Auction Mart. They were a similar distance from the Gas Works. The petitioners were not influential – only half were ratepayers. Similar objections were clearly going to arise, whatever site was chosen. So in September 1886 it was decided to proceed. Plans were drawn up, and funding obtained in the form of a loan of £1,050. The Fever Hospital was ready to be occupied in 1888.

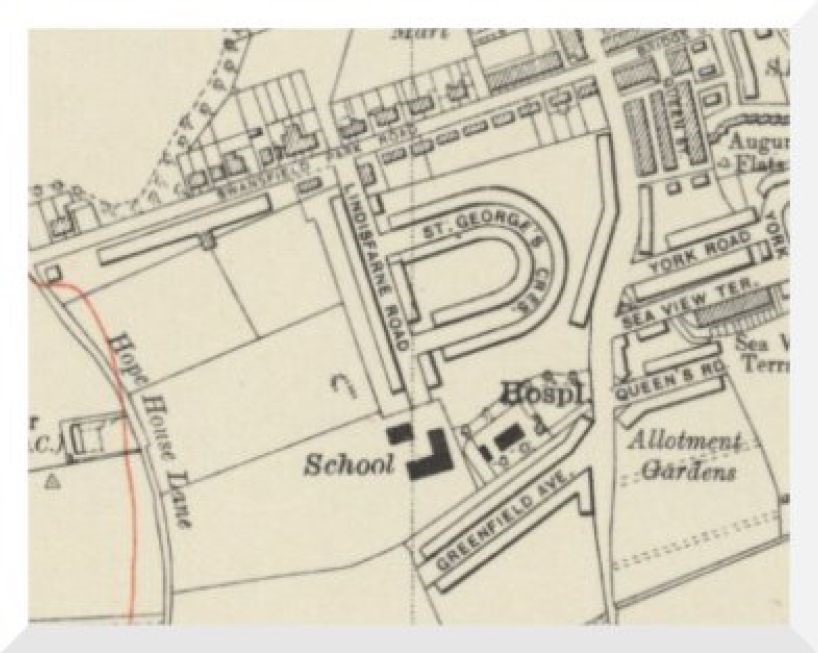

The Ordnance Survey map of 1897 shows the fever hospital at some distance from Bridge Street, and other housing on Wagonway Road, but new development on Swansfield Park Road is already marked out, and would bring housing closer. By 1938, when the Ordnance Survey updated the map, housing was starting to surround the fever hospital. Alnwick County Secondary School (later Lindisfarne Middle School) had been built alongside, and would open in 1939. Fears of contagion must have diminished.

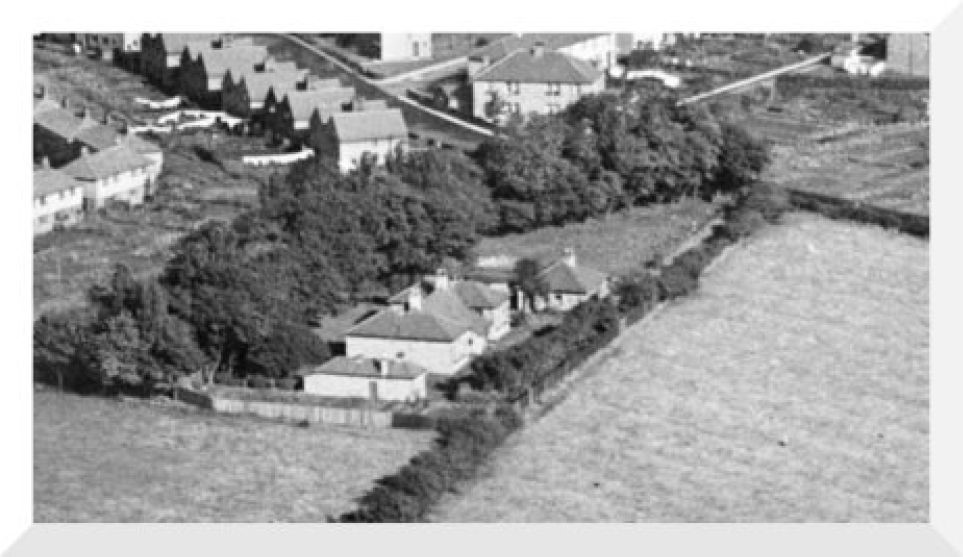

This picture shows the Fever Hospital in 1932. St George’s housing is to the left and Wagonway Road above. We know there were two wards, and half a dozen beds (including cots for children), and there was a lodge to help keep the contagious patients separated from the general public.

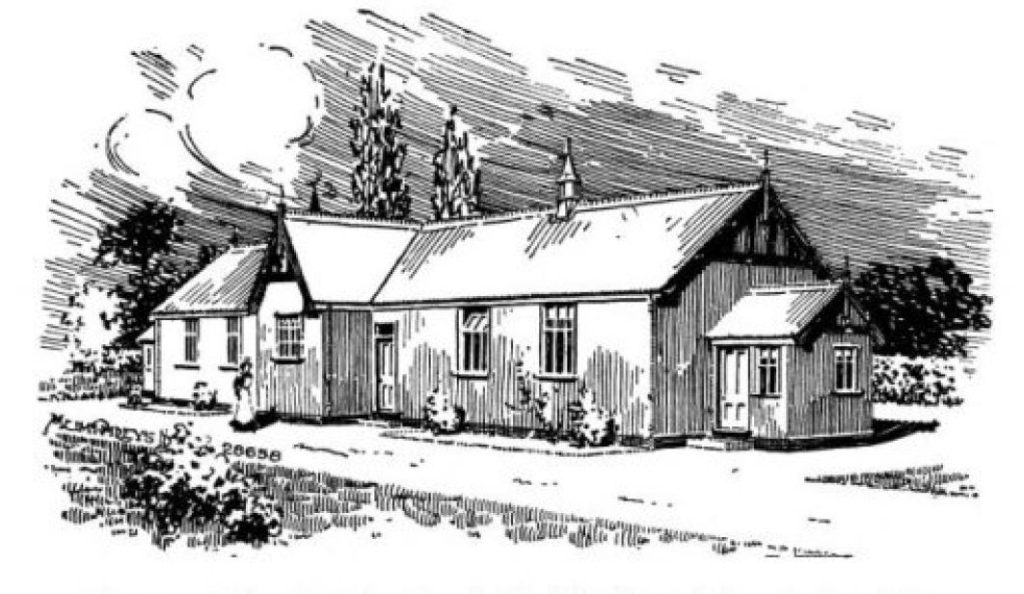

Nationally, the Local Government Board was developing standard model plans for isolation hospitals in different types of town. We know from these that rural isolation hospitals were typically small, and attractively laid out like detached villas. This was in contrast to those in larger conurbations which tended to have parallel rows of detached wards, described as “pavilions” and designed to allow free movement of air. Similar plans suggested by the Local Government Board show a small building for four patients, with central accommodation for nurses over two floors, and two single-storey wards, each with a large verandah. They include a detached laundry and mortuary.

Over time, facilities were improved, but the Fever Hospital seems to have provided enough capacity to meet the usual level of need. We don’t have a complete record, but in a year when the medical officer recorded that they wanted to isolate some patients they typically transferred between half-a-dozen and a dozen cases to the Fever Hospital. The highest number we have found was in 1925 when the hospital handled 22 patients.

In some years the Medical officer records a small number of patients suffering from Tuberculosis or Smallpox being transferred elsewhere. The patients at the Fever Hospital were mostly suffering from Scarlet Fever (two-thirds) or Diphtheria (one-third). Exceptions included two children in 1899 who were simply “removed from a damp and otherwise insanitary room”, one case of Puerperal Fever in 1937, and one of Vincent Angina (trench mouth) in 1943.

The Medical Officer of Health occasionally complained about the facilities, but rarely about capacity. One example was in 1908, when the hospital was fully occupied dealing with Diphtheria. There had been no serious outbreak of Scarlet Fever for almost a decade, and the Medical Officer of Health was expecting one. If that happened he was not confident that he could isolate sufficient patients. After he wrote his report two patients were admitted for Diphtheria then developed symptoms of Scarlet Fever. They had to be

isolated in one ward, while the ordinary Diphtheria patients occupied the other. In effect the hospital was closed to further cases. All the subsequent Scarlet Fever patients had to be isolated at home.

The use of isolation hospitals declined in the 1940s as antibiotics were increasingly used to treat infectious diseases. The last patient was admitted to Alnwick Fever Hospital in 1952. After that it was no longer needed. The site was transferred to the Education Board, and used for the extensions to Lindisfarne School in 1959. The Sports Hall now stands where the Fever Hospital once was.

Pete Reed, from an article in the Alnwick Civic Society newsletter, April/May 2020