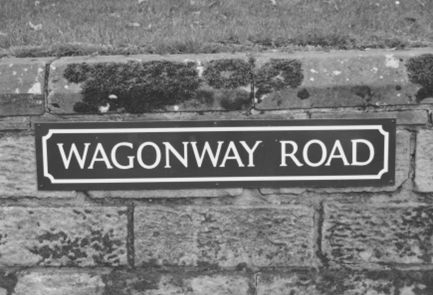

Coal had been mined in bell-pits around Alnwick since at least the mid-16th century. By the 19th century deeper mines were being worked at Shilbottle. In 1809 a metal wagonway was opened from Shilbottle to Alnwick which reduced the price of coal to the local inhabitants by about half. The wagonway ran to the east of what is now Wagonway Road, and terminated at a staithe near to where the station would later be built. The wagonway was closed by the early 1850s.

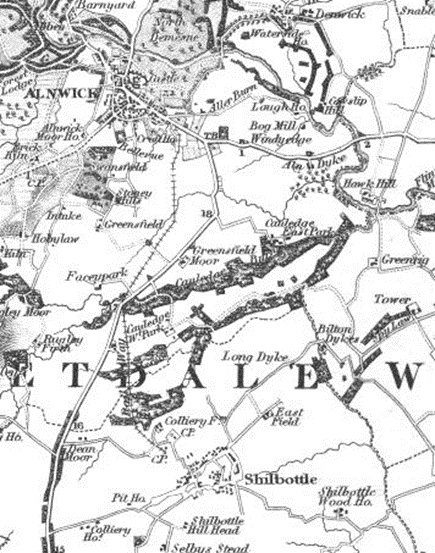

Coal mining in the Alnwick area began in the 16th century using ‘bell pits’. Carts, pulled by horses, took away the coal for sale in Alnwick and its surroundings. Shilbottle coal was popular as it burned with a bright flame, thus producing both heat and light. The pit which served the first Shilbottle to Alnwick Wagonway was sunk in 1807; it assumed the name of ‘Shilbottle Colliery’ which had been applied to other pits earlier. The waggonway, sometimes referred to as a ‘railroad’, was constructed at the expense of the colliery lessee, Mr. John Taylor. It, was reported as being opened on 5th May 1809 when the first wagonloads of coal were transported over the cast iron rails to a ‘staith’ close to the start of what is now ‘Wagonway Road’ near to the future site of Alnwick Station. The line resulted in the immediate reduction in price of the coal, in that the previously exorbitant charges imposed by the cartmen, were now considerably reduced. This had the effect of making the coal affordable to many more of the poorer inhabitants of the town. The line appears on Greenwood’s Map of Northumberland dated 1829 and the Tithe Maps of 1844.

From the colliery at Shilbottle it followed a north-westerly course, crossing the Great North Road near Cawledge, following an east route across several fields before passing along the alignment of the present-day Wagonway Road (sic) as far as the staith.

Gravity assisted the horse-drawn wagons as far as Cawledge. Thereafter there was a gentle rise, a level portion and a gentle fall to the terminus.

The wooden wagons could hold 60 hundredweight of coal (3 tons) and they had handbrakes which were operated by a boy who walked along at the sides of the wagon. Various lengths of well-rusted iron have been excavated from the alignment of the wagonway and these have been identified by experts from the National Railway Museum as being likely to have been fragments of the original rails. Being cast iron the rails were prone to fracture and it is likely that the fractured portions were simply discarded at the side of the track when new lengths of rail were installed.

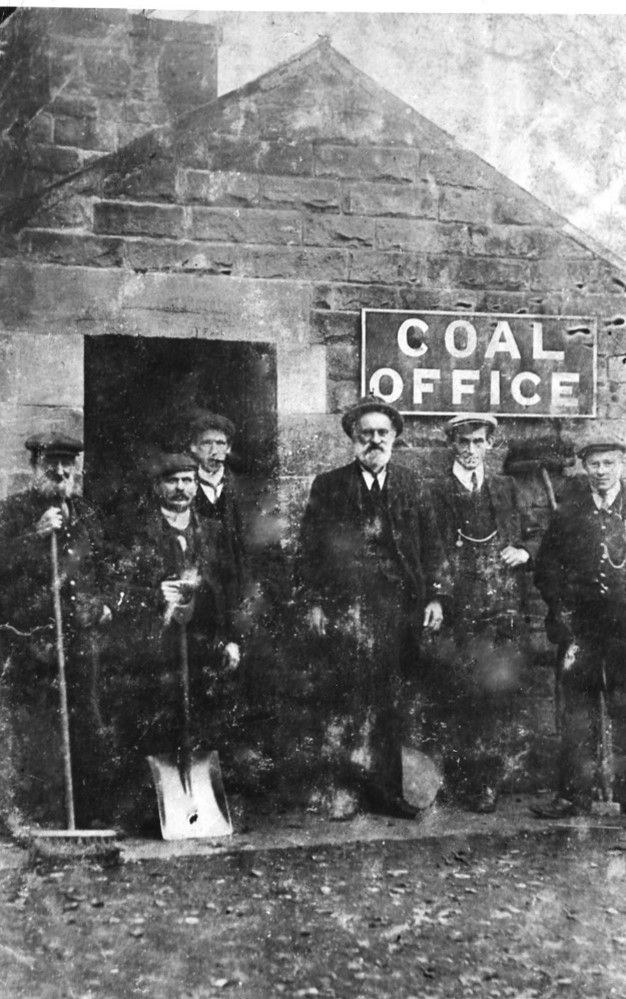

The Duke of Northumberland was paid a rental charge of £210 annually for the colliery and 4½d (about 2p) for each ton of coal raised. There was no wayleave charge for the wagons passing over the Duke’s land. Purchased at the pit mouth coal was available for 7s 6d per ton. At the staith an additional 2/6d was charged and for delivery into the town by cart a further one shilling making the total in-town cost 11 shillings per ton. An article in an 1860 edition of the Alnwick Journal referred to the fact that ‘…once upon a time … (the coal) … was carried through the town in cuddy carts by superannuated individuals , who retailed it in ‘pokes’ containing five halfpence worth, (1p in today’s money!).

The precise date of closure of the line appears to have gone unrecorded though it certainly took place in the late 1840s or early 1850s. The present-day Colliery Farm lies adjacent to the former pit site and several of the nearby buildings belonged to the colliery including the stable building which housed the horses used on the line. Some remains of much-eroded former spoil tips exist.

The route across the fields has largely disappeared though can be followed partly with aid of old maps. Wagonway Road follows the route of the final portion of the line.